Column: NC’s 20th century political dynasty offers lessons for today

Published 12:48 pm Thursday, May 23, 2019

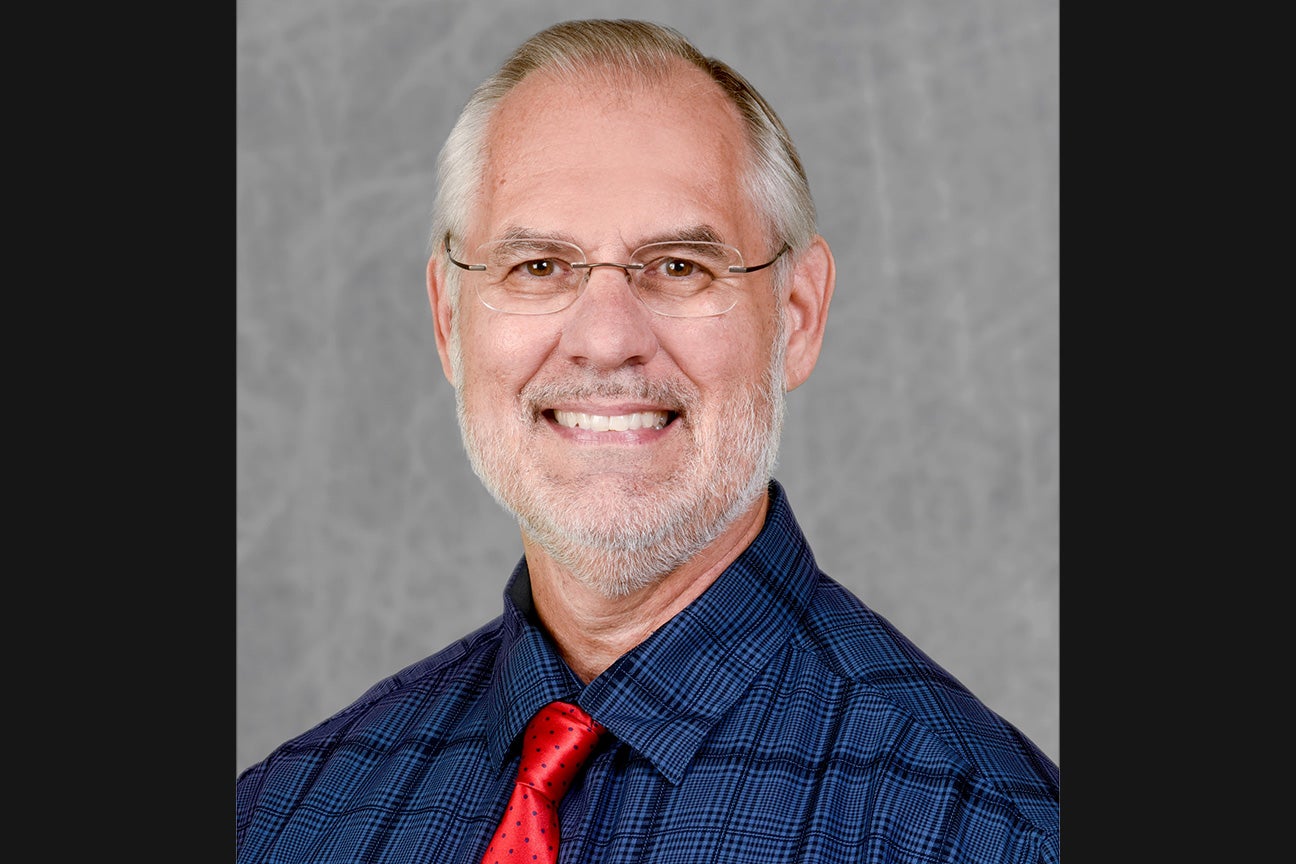

by Colin Campbell

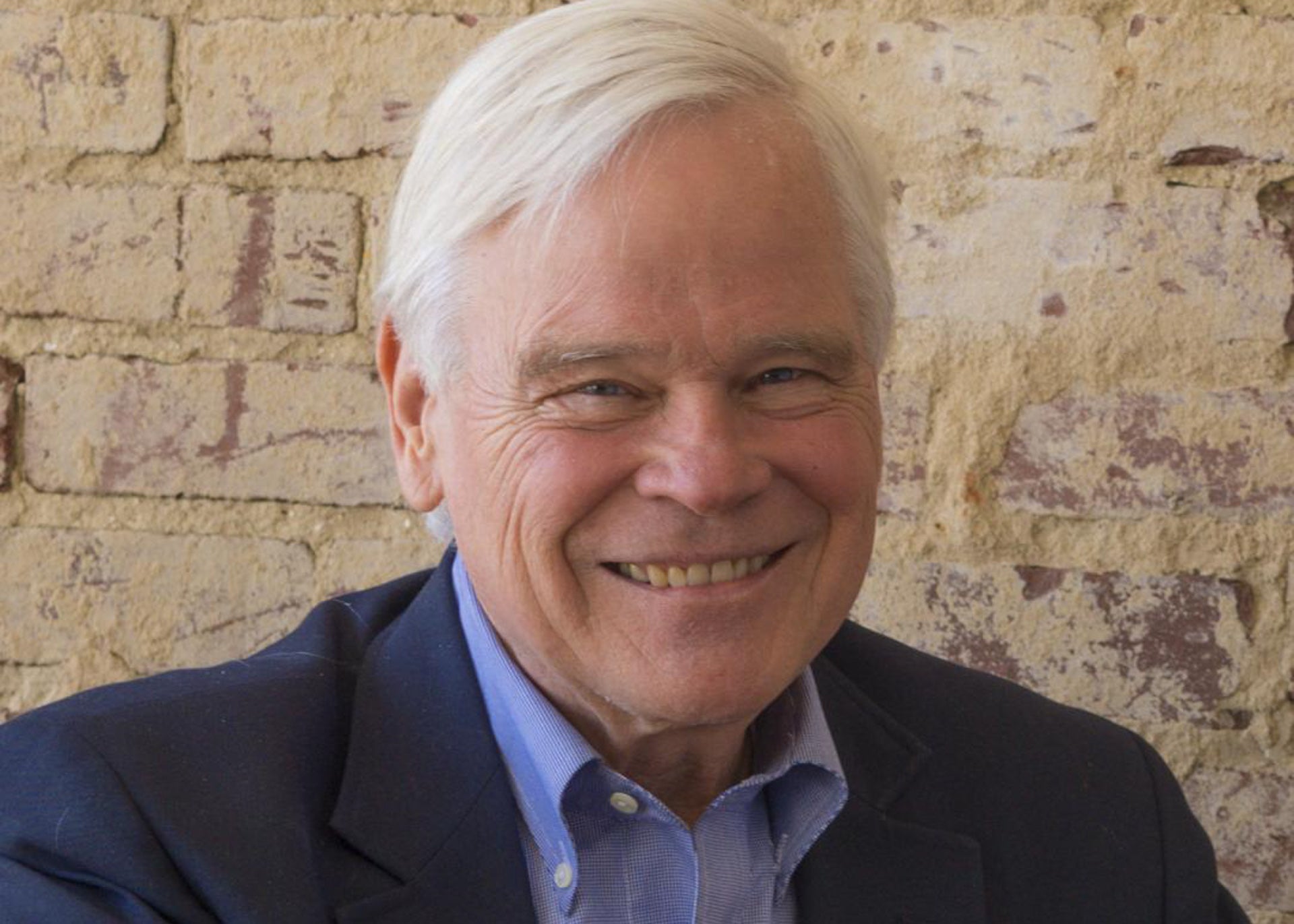

As Rob Christensen researched his new book on a North Carolina political dynasty, a window opened into a tumultuous period of state history.

Christensen, a retired political journalist and columnist for The News & Observer, discovered that Gov. Bob Scott – in office from 1969 through 1972 – had kept a meticulous diary of his time in office. Scott had ordered the diary to be sealed until after his death in 2009, and Christensen was the first to read it.

Scott’s tenure included the public school integration process, in which he tried to take a moderate approach.

“He says, ‘You’ll probably wonder what in the world was going on with busing and why it was such a huge issue,'” Christensen said of the diary. “‘And I hope you understand as you write about this, the temper of the times, and that I really didn’t have a lot of options.’ It was interesting that he sort of wrote a note to future historians saying, give me a little understanding here.”

Christensen’s new book, “The Rise and Fall of the Branchhead Boys: North Carolina’s Scott Family and the Era of Progressive Politics,” traces the family’s history over the 20th century. It features Bob Scott and his father, Kerr Scott, who was both North Carolina governor and senator, as well as Bob Scott’s daughter, Meg Scott Phipps, who was elected agriculture commissioner in 2000 before going to prison a few years later for campaign finance violations.

I spoke with Christensen before the book’s publication.

Q: Out of all the key figures in North Carolina political history, why did you decide to focus on the Scott family?

A: A lot of states have a particular family that’s played a particularly important role. You think about the Longs of Louisiana or the Talmadges of Georgia or the Kennedys of Massachusetts, and the closest equivalent we have to that is the Scotts of North Carolina.

Their influence was more than just the family. Terry Sanford really got his start with statewide politics as a campaign manager for Kerr Scott, and there’s a picture of a (young) Jim Hunt going in the (governor’s) mansion and meeting Kerr Scott. And what all these had in common is they were all from rural North Carolina.

Q: How did the “Branchhead Boys” name come about?

A: Kerr Scott called his supporters the “Branchhead Boys,” or those people that lived at the head of the branch or the head of the creek, and therefore the most rural people. He had a Democratic but a very conservative and hostile legislature he dealt with, and he was one of the first to go over their heads – directly to the people – whether it was through radio broadcasts, or bringing huge rallies into Raleigh.

When Kerr Scott came along, people were demanding that the government come in and help them. Government was seen as something good – have the government come in and help pave my road so I can get to the doctor’s office, or have the government push the power companies to extend telephone lines and electric lines. So the people in rural North Carolina were demanding that their government become an activist government.

But 20 years later, in 1968, by the time Kerr Scott’s son (Gov. Bob Scott) was elected, it was an entirely different story. By ’68, people were saying, “Government, leave me alone.” And so they were beginning to switch off the Democrats and began voting for people like Jesse Helms, George Wallace, Richard Nixon, and now today, Donald Trump.

Q: How did the Scotts manage to walk the line on the segregation and racial issues that were so key during their decades in politics?

A: It was very difficult. The Scotts had always been progressive for their time. That’s not to say they were for ending segregation. No public official in that era was. But Kerr Scott appointed the first black to a major state position, the president of St. Augustine’s College to the State Board of Education. In 1949, that was revolutionary. He would meet with groups like the NAACP, and it seems totally unremarkable today. But at the time, the NAACP was seen as almost a pro-communist organization.

Kerr Scott misread how far he could go. And so he essentially got out in front and was pushing the state, in the post-war era, to become more progressive on race . . . So by the time he got to the United States Senate, he was voting along with most of the Southern senators in terms of opposing almost any civil rights legislation.

His son Bob Scott had the same problems, even though it was a different era. So he came out as a very, very tough guy, and he moved to the political right, which is what enabled him to get elected. He had no compunction about calling in armed forces and sending them to campuses to restore order.

Q: What sort of lessons, particularly on the urban-rural divide issue, does the Scotts’ legacy leave for our current crop of leaders in North Carolina?

A: It’s puzzling that rural areas are still struggling to compete with the urban areas, and yet, their political leaders don’t seem to recognize the importance of activist government to help the rural areas. The rural areas need the help more than the urban areas.

Some of the lessons for the Democrats is that Kerr Scott lived all his life on a dairy farm, and every weekend, he went back – even as governor. And so he was always very close to his constituents. He was a big hunter, he was very religious. He often talked about things in kind of a religious way. So he could push forward his progressive program in a way that was culturally acceptable to people who are more conservative, because he understood people, and he also understood their needs.

Colin Campbell is editor of the Insider State Government News Service. Write to him at ccampbell@ncinsider.com.

FOR MORE COLUMNS AND LETTERS TO THE EDITOR, CHECK OUT OUR OPINION SECTION.