A family’s remarkable record of service

Published 10:46 am Wednesday, February 17, 2021

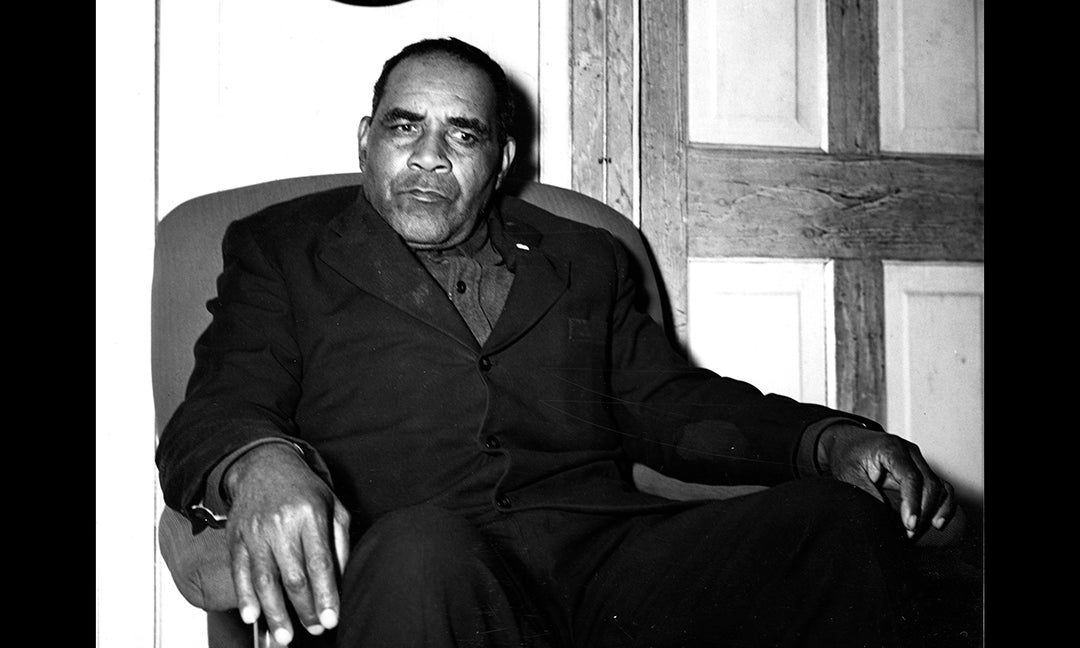

- Joseph Hall Berry, the patriarch of a remarkable record of service. Courtesy Joan Collins

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Joan L. Collins

Many, especially locals who live on the Outer Banks, are aware of the story of Keeper Richard Etheridge and the Pea Island Lifesavers. A life-sized bronze statue of Etheridge, a slave who became the nation’s first black keeper, is prominently displayed at a street roundabout in Manteo. The Pea Island Cookhouse Museum, who most know simply as the “Cookhouse,” is located directly across the street. Next to the museum is the Herbert M. Collins Boathouse. These attractions honor the history of Keeper Etheridge and the black lifesavers who worked at Pea Island, a station that operated when the US Life-Saving Service (USLSS) existed and later during the early US Coast Guard. The lifesaving station on Pea Island was the only all-black station in the history of the USLSS and one of only two all-black stations in the history of the Coast Guard. As Black History Month is celebrated, it is an especially important time to remember the contributions that blacks have made in their struggle for freedom and equality. It is also an ideal time to bring attention to the contributions blacks have made that are not widely known.

If you have ever visited the Cookhouse, you may have noticed this photograph of a man sitting in a chair. It hangs in a small back room. In the same room on an adjoining wall hangs a replica of the Gold Lifesaving Medal that Keeper Etheridge and his crew received one hundred years after their daring October 11, 1896, rescue of the shipwrecked schooner E.S. Newman during hurricane conditions. The man in the photograph is Joseph Hall Berry, who once served as a temporary surfman under Etheridge. Sitting above his chair is an oval shaped framed picture showing him as a young man. Ironically, on February 1, 1902, the same day that today is the start of Black History Month, he enlisted in the service. He served as a permanent surfman at the Pea Island station when it was part of the USLSS and later when it became a Coast Guard station and until he retired in 1917. Twenty members of his immediate family followed his footsteps and joined the service, creating a remarkable record of combined service his family has – some 400 years. Joseph Hall Berry was my great-grandfather.

Maxie M. Berry Sr., who was Joseph Hall Berry’s son, was the last officer in charge at the Pea Island station. He had one son, fourteen grandsons, four great-grandsons, and one great-grea-grandson to also serve in the Coast Guard.

One grandson, Maxie M. Berry Jr., retired as a Lieutenant Commander, the highest rank of any Berry family member. He became the first black in charge of the Office of Civil Rights at Coast Guard headquarters in Washington, DC. Hubert Z. Collins, another grandson (the twin brother of Herbert M. Collins) bravely fought in battles during several invasions in World War II. His grandson Joseph McKinley Berry served during three wars – World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Another grandson, Vincent Collins, served on a Coast Guard icebreaker and was sent on voyages in the north and south poles. Joseph Hall Berry’s great-grandson Ralph Berry became the first black diver in the Coast Guard. Another worked at the Coast Guard Academy wishing he was a cadet, yet knowing he would never be able to attend. The list goes on and on of Berry family members who served in the Coast Guard following the footsteps of Joseph Hall Berry, a man who began his service under Keeper Etheridge.

What most do not know, or may have never taken the opportunity to read while visiting the Cookhouse, is that next to Joseph Hall Berry’s photograph and in the same frame is yet another important reminder of the history of Pea Island, a typed letter he wrote years ago. The letter, dated July 6, 1939, is addressed to Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt. It was written shortly after the First Lady had visited the Goose-Wing Club where his son-in-law, Marshall Collins, worked as a cook. The letter was written when a white officer had been transferred to the station and when another white man was added to the crew. Berry wrote in the letter when it was rumored “that the plan was to gradually remove the colored men from the station and turn the station over to white men.” Believing that Mrs. Roosevelt would be sympathetic, Berry hoped the First Lady would intervene “to preserve for America its only Coast Guard Station, under the direction of an all-colored crew.” Needless to say, I was happy and quite excited to discover this letter while reviewing my grandfather’s Coast Guard record a few years ago and to bring it to the attention of the Coast Guard Historian’s Office.

Although it is not known if the July 6, 1939, letter ever reached the First Lady, about six months later, his grandson Herbert M. Collins, who had been serving as a Mess Attendant on a ship, was transferred to serve as a surfman at Pea Island. But after working at Pea Island for about three months, he was transferred to serve as a Mess Attendant on his third ship. Some eight months later, he was transferred back to Pea Island where he served as a surfman the duration of World War II. When Herbert M. Collins worked at Pea Island, initially he served under a couple of white officers. In 1937 white officers were being placed in charge of the station. However, a few years later, Maxie M. Berry Sr., who had been working at the station for several years, became the acting officer in charge and was officially advanced to the position of Chief Boatswain’s Mate on November 1, 1943. He retired shortly before the station was decommissioned in March 1947. Herbert M. Collins, who at the time was serving as a Boatswain’s Mate, First Class, was the last person left to remain at the station before it closed. He remained assigned there for a couple of months to prepare final paperwork and to help decommission the station. A few years later, on January 16, 1951, Joseph Hall Berry died, but he had lived to his son and his grandson to serve at Pea Island. By the time of his death, other grandsons had also joined the service. The Berry family remarkable record of service was well underway.

Surfman Benjamin Wesley’s photograph was recently donated to the Cookhouse Museum. Courtesy Joan Collins

Recently, I was excited to learn of another photograph of a black man who served at the Pea Island station, a photograph I had never seen since I began researching the station’s history after my father died in 2010. The call was from a lady whose son had visited the Cookhouse this past summer. She said she had a photograph of her grandfather in uniform that she wanted to donate to the Cookhouse. I was even more excited when I visited her in Maryland this past December and picked up the photograph of her grandfather, Surfman Benjamin Wesley who had served at the station sometime in the 1930s. It was in an old cardboard frame with a few scratches, but otherwise in good condition. Yet another reminder of the many blacks who served at the station long after Keeper Richard Etheridge died.

People who have photographs, artifacts or other information about the Pea Island station are urged to contact the non-profit organization, Pea Island Preservation Society, Inc., otherwise known as PIPSI. The organization’s email is friends@peaislandpreservationsociety.com. Black History Month is a perfect time to help PIPSI make this history known.

Joan Collins serves as the Director of Outreach and Education for PIPSI. This article is based on her research of her family’s Coast Guard records and other information about the historic station.

READ ABOUT MORE NEWS AND EVENTS HERE.

RECENT HEADLINES:

Oregon Inlet and Hatteras Inlet badly shoaled, dredging coming this month