The Nature Corner: The Outer Banks

Published 8:15 am Sunday, September 29, 2019

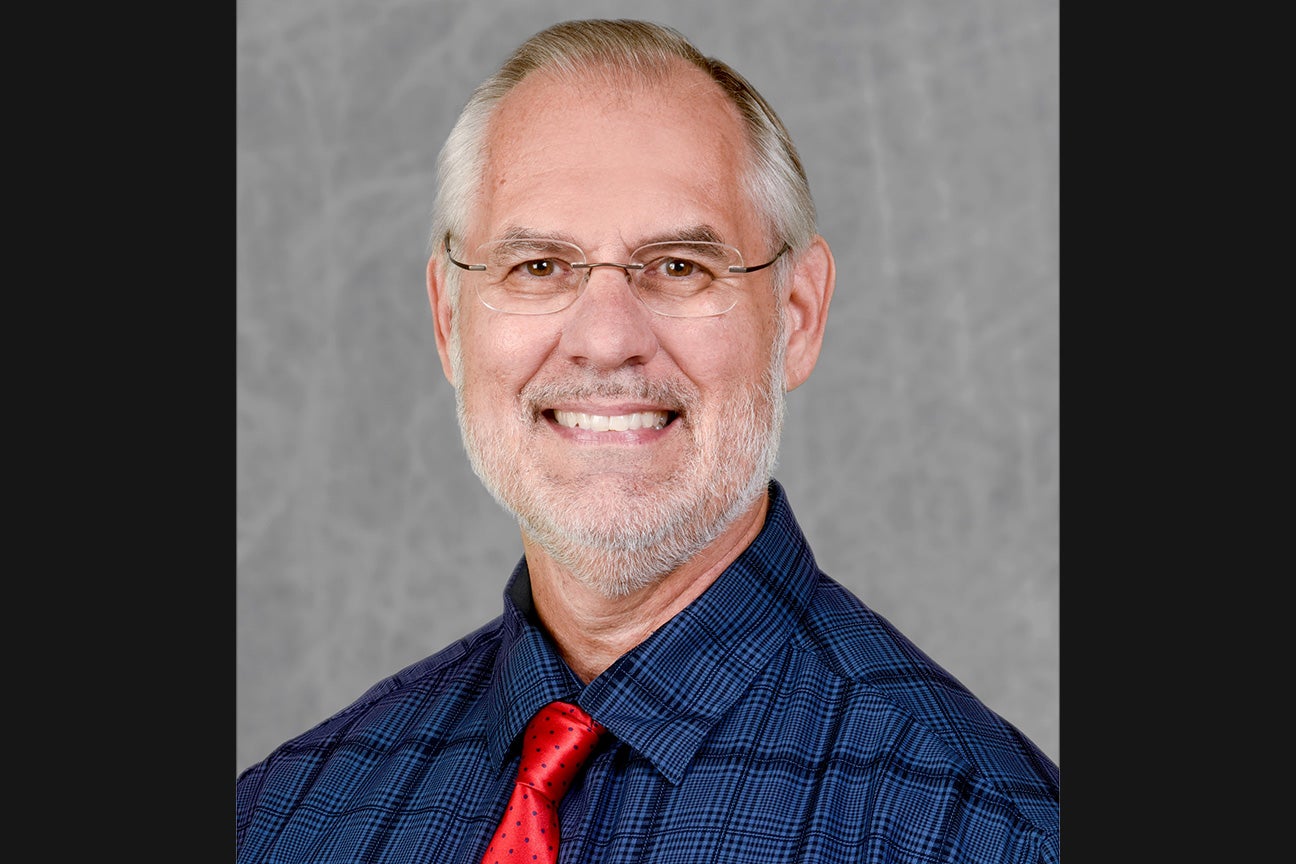

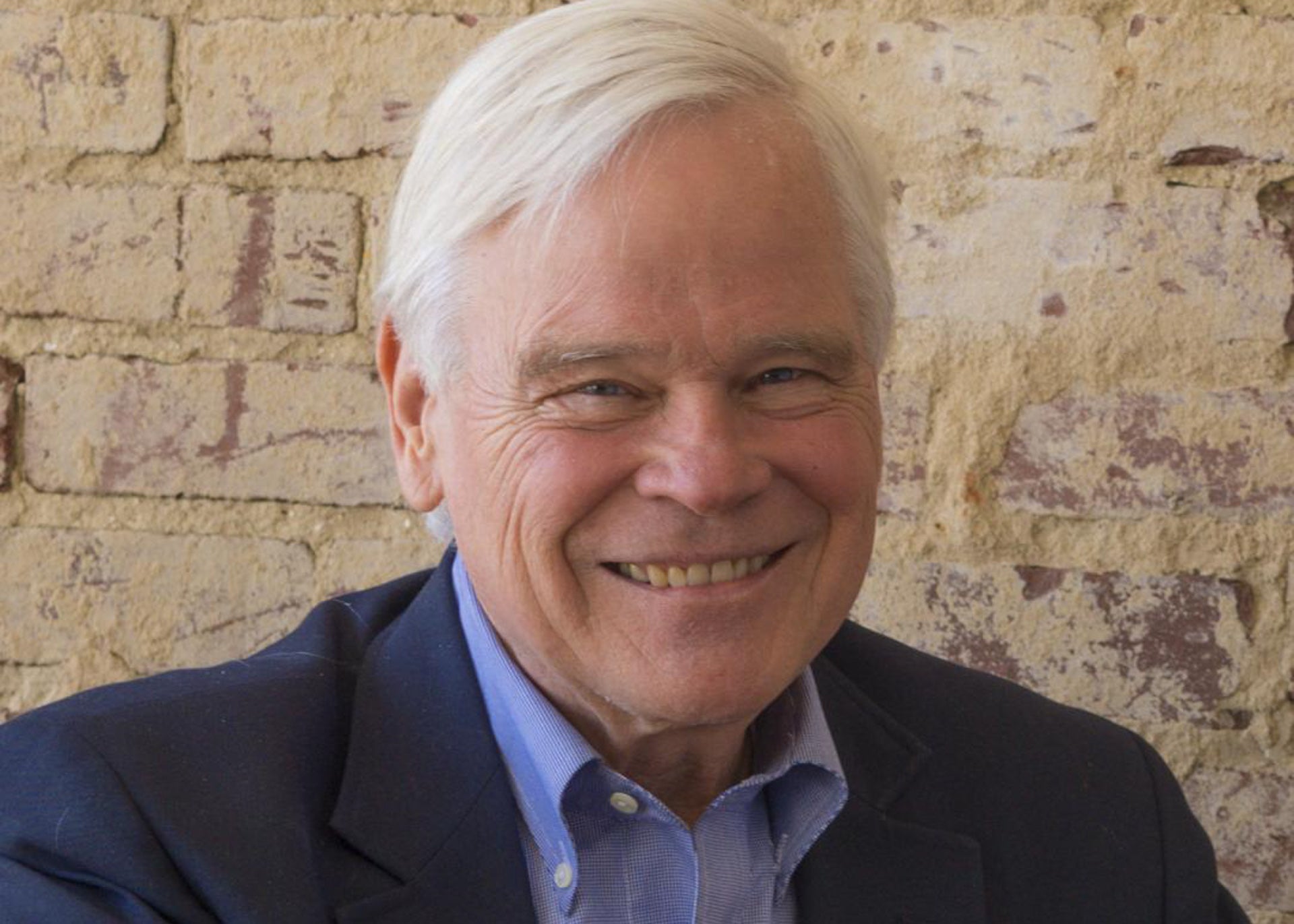

By Ernie Marshall

What is the official state seashell of North Carolina? Answer at the end of the column.

The Outer Banks and their associated sounds and estuaries are one of the natural marvels of the North American continent. It is a chain of barrier islands (about 22 islands) some 200 miles long. The Outer Banks have been called “a ribbon of sand” because of its dynamic character, reshaping itself over time from taking it on the chin from the Atlantic Ocean (relentless buffeting waves, wind and tide, nor’easters, hurricanes, etc.), but also learning to roll with the punches.

These barrier islands are remarkable because only about 13-15% of the world’s coastlines have barrier islands. Those of the North Carolina coast are part of a continuous system from New England (which has a rocky rather than sandy coast because the Appalachian Mountains at that point meet the sea), all along the Atlantic Coast, the Gulf Coast and on down into Mexico.

These barrier islands do three very important things for us. First of all, as the word “barrier islands” implies, they protect the mainland from Poseidon’s wrath, the full force of the Atlantic Ocean, hurricane storm surges and all the rest. Secondly, they create a brackish estuary environment on their mainland side, choice nursery grounds for many aquatic creatures, including fin fish and shell fish critical to our fishing industry and sports fishing and also winter waterfowl hunting habitat. Last, and perhaps not least, our Outer Banks are a recreational paradise for residents as well as visitors who support a thriving tourist industry.

Our Outer Banks are a place to explore and enjoy, but also to preserve. I think the northern Outer Banks have struck a good balance between these objectives. Villages such as Rodanthe, Salvo, Buxton and Hatteras cohabit well with the National Seashore. The public supports protecting sea turtle hatchings and the ecosystem they share with other of Earth’s inhabitants.

In our zeal to protect our property against the changing ways of this dynamic system, we sometimes do unintended harm, for instance, seawalls may temporarily protect a building, but contribute to the loss of a beach.

My favorite Outer Banks experience has to be a weekend canoe camping trip with my daughter Stephanie from near Beaufort to Shackelford Banks. The island had been recently acquired by the National Park Service as part of the Cape Lookout National Seashore. It was utterly undeveloped and gave the impression that this was the Outer Banks in all their native innocence. We didn’t see another human being for the entire three days, only pelicans, gulls and shorebirds, ghost crabs scurrying about, an occasional group of dolphins gracefully passing like a ballet troop and a flock of six sheep.

The sheep were led by a big black ram with an impressive pair of curled horns. There was no question that he was not only in charge of his harem of ewes but also the entire island!

As we went about our day, camp chores or exploring the island, we had the uncanny feeling that we were being watched. Out in the middle of nowhere? Sure enough, there was that big black ram on the tallest nearby dune intently watching us.

Our Outer Banks have for centuries been home to surviving livestock brought to America in the days of European exploration and colonization. The horses, “Island Ponies,” are those most famous, but this wilderness stockyard includes other animals, many of which survived from shipwrecks. Ships coming to “the New World” often had a veritable ark on board, much of it for fresh food for the lengthy sea voyage. Livestock were also being transported by those planning to establish a settlement. Barrier islands were also utilized as a place to range animals. Sound waters served as fencing. A cycle completes itself. Animals once wild were domesticated by humans and centuries later are by historical circumstance returned to the wild.

Stephanie and I had planned on doing some surf fishing, but sure enough I left our fishing gear behind. We spent most of our time “shelling” or shell collecting anyway. Anyone who has had our rare opportunity to look for sea shells on a deserted beach, literally untouched by human hands, knows what an abundance awaits. It is an accumulation of shells from years of incoming waves, nor’easters and hurricanes. My daughter was an avid shell collector, so was the proverbial kid in a candy store.

A beach is a boneyard. What we loosely call “seashells” are mostly the exoskeletons of mollusks washed ashore. There are some clams and mussels in our fresh water lakes and streams, but most of this very large phylum of invertebrates live in our oceans. Some are seafood favorites such as oysters, scallops, mussels, clams and squid (calamari), octopus, welks (conch) and snails (escargot) for the more adventurous. Other “seashells” are better known to shell collectors, angel wings, arks shells, cockles, baby’s ears, augers, shark eye’s, olive shells and oyster drills, to name a few.

Among other collectables, creatures from the sea other than mollusks, are sand dollars, starfish (“sea stars” is better, since they are not fish), “mermaid’s necklaces” or welk egg cases, “mermaid purses” or skate egg cases and horseshoe crabs (“living fossils” more closely related to scorpions and spiders than crabs).

On the return paddle to the mainland, we had to make room for a garbage bag full of seashells. Stephanie’s favorite was a large glossy gray knobbed welk she called “Black Beauty,” which to this day is displayed on a bookcase in her bedroom.

You know what? If you hold it to your ear I think you really can hear the ocean and maybe even a sheep bleating in the background.

The official state seashell of North Carolina is the Scotch Bonnet.

Ernie Marshall taught at East Carolina College for thirty-two years and had a home in Hyde County near Swan Quarter. He has done extensive volunteer work at the Mattamuskeet, Pocosin Lakes and Swan Quarter refuges and was chief script writer for wildlife documentaries by STRS Productions on the coastal U.S. National Wildlife Refuges, mostly located on the Outer Banks. Questions or comments? Contact the author at marshalle1922@gmail.com.

FOR MORE COLUMNS AND LETTERS TO THE EDITOR, CHECK OUT OUR OPINION SECTION HERE.