Man reunited with rod and reel 50 years after Outer Banks fishing trip took a turn for the worse

Published 8:26 am Tuesday, October 4, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In the mid-1970s, Dennis Dudley was visiting his then-brother-in-law Russell Twiford at his Nags Head cottage when a unique fishing rod and reel caught his eye.

It was about 9 feet long and hanging on the wall like a show piece. Dudley said Twiford told him it was found in a commercial fishing vessel’s net. “I was admiring it and he said, ‘Why don’t you take it home?’” Dudley recalled.

The reel was a Fin-Nor 4, a Miami-based company, and very high-end for the 1970s. It was engraved with the name Ralph E. Vodicka. The rod was a 9-foot spinning rod.

“I have lots of fishing equipment and nothing with my name engraved on it,” Dudley said. It must have been a special piece, and he figured the owner would want it back.

And so the search began. But it would be almost 50 years before Dudley returned the gear to its rightful owner.

He asked around, but none of Dudley’s friends had heard of Ralph Vodicka. He wasn’t in the local phone book.

Twiford had mentioned that Vodicka was a saltwater editor for Sports Afield magazine out of southern California, so Dudley started there. He wrote a letter explaining the story and asking for contact information.

No response ever came. (Vodicka never did work for Sports Afield—it had been an unintentional rumor that was passed along with the fishing rod. But Dudley wouldn’t discover this for many decades.)

“Quite frankly, I didn’t know what to do after that,” he said.

It was before the days of the internet and worldwide searches. Dudley had no other leads, and so he hung the Fin-Nor up on his own wall in his Elizabeth City home. The years turned into decades, and he forgot about the search for the owner of the mysterious rod and reel.

And then it was the days of the internet and worldwide searches.

Dudley, now 78, and his wife began to look around at the items in their home with fresh eyes. “Our years are limited,” he said. “We’re looking at things like, what do we pass on, what do we find new homes for?”

His gaze rested on that old fishing rod, and he examined the engraved name plate on the reel once again. He hadn’t thought about it in a long time.

He walked over to his computer and typed “Ralph Vodicka” into the Google search bar.

He was startled to read that a Ralph Vodicka, age 89, was alive and well in Raleigh, North Carolina. Dudley found his phone number, dialed him up and left a message, asking him if he lost a rod and a Fin-Nor fishing reel in the early 1970s.

“I was amazed he even returned my call, with the crazy story I’d left on his machine,” Dudley said.

If Vodicka was skeptical at first, “he soon got convinced” Dudley was in possession of his favorite rod that was lost so many years ago, Dudley said. “He wanted to know if he could buy it and I said no. It was his.”

The men agreed to meet up halfway at a Cracker Barrel in Rocky Mount. They ended up talking all afternoon and swapping fishing stories, including the one Dudley had waited over 50 years to hear—how that beautiful rod and reel ended up in a commercial fisherman’s net.

Vodicka settled in and told the story, which he remembers with astonishing detail.

It was a deceptively fair day on the water. Vodicka and three friends headed out for a fishing trip off Hatteras National Seashore in a 17-foot, 1966 Boston Whaler. He’d been working for IBM for about 15 years, first as an engineer when the early computers were being built, and then as a salesman. He’d been transferred to the research triangle in Raleigh while he worked on developing and implementing technology for point-of-sale machines for major grocery chains.

He’d navigated inlets hundreds of times in Florida, but the Oregon Inlet was unfamiliar. He studied his depth chart. He should have been at about 40 feet. He felt alright about 40 feet. But in reality, he recalled later, he was only at a depth of maybe 15-20 feet.

It was about 4 p.m. and Vodicka was offshore several miles. “The waves were just rolling—not breaking. I saw a big trawling boat go through the inlet. He was bobbing and wheeling all over the place. I said, ‘Holy smokes, we’d better get in [the inlet] or we’ll be doing this at night.’”

The tide was running out. It had big swells that were running in—swells from a big round top to breaking waves, he remembered. “It was a little risky being out in a 16 or 17 foot boat. But I was at an age when I couldn’t be killed.”

As every inlet angler knows, the choice is to wait until the tide turns, or take your chances.

“Waiting it out would put us in the middle of the night. We decided that the best choice was to race on in while we could see. I told everyone, ‘Hold on, don’t move. We’ll ride on the back of one of the breaking waves. Even if it takes a little water, it’ll be ok.’”

The idea is to ride in on the backside of a wave, careful to maintain the same speed of the wave and not to get ahead of it.

But halfway through, Vodicka said, the motor started to die. One of his friends had decided to start bailing and somehow a line got caught up in the prop, causing it to stop turning.

An 8-ft breaking wave rushed in and flipped the boat end to end.

One man was thrown 15 feet into the air ahead of the boat into the water. Two others miraculously clung on. Vodicka got trapped underneath the boat between the console and the 12-gallon gas tank, wrapped in fishing line and struggling to break free. Every time a wave would come in, the gas tank would shift and crash into his stomach. It was a desperate fight for life and he was running out of oxygen.

Finally, the lines came loose and he bolted to the surface, gasping for air.

Meanwhile, the captain of an old 25-foot boat was out with his grandson when he saw what happened and came toward them. The man who was thrown from the boat started swimming. The captain tossed him a rope and pulled him in before a breaking wave overtook him.

“He got into the boat, and my buddy talked him into coming back. He had to time it just right so he didn’t get hit with those big breakers. That boat had no business doing what he did. It was not a sturdy boat. He was taking tremendous risk.”

But he turned back around to rescue Vodicka.

“I swam like a demon. Back in those days I was a great swimmer. I swam and got into the boat, asked him if he had lines or lifejackets. I got a long line and lifejacket, and persuaded him to go back for the other two. We figured we could only do one at a time. We were hollering at them, threw the lifejacket in, and pulled him in real quick. We had to take off real quick, then came back for the last man.”

“He was as white as a sheet. He was hanging on the prop and wouldn’t let go. The [boat captain] said ‘I’m only going one more time. I can’t risk my grandson.’ So I said to my buddy, ‘This is your last chance.’ I didn’t want him to die out there and that’s probably what would have happened. All of sudden, like a windmill, he came toward the boat, and we pulled him in.”

The survivors were taken to the Oregon Inlet Coast Guard Station, where they were offered hot showers and were allowed to wash and dry their clothes. Vodicka watched from the station as his boat was beaten and battered by the waves.

The Coast Guard tried to retrieve the boat but the waves kept threatening to flip it. Finally, they tried a duck boat—a land and sea vessel that would right itself in rough water. Vodicka said it flipped over three times with men strapped into it.

He remembers one of the ranking officers saying, “Mr. Vodicka, that’s about all these guys can take. Will you give permission to call them back in?”

According to Vodicka, in those days, the man who ran the station kept his men out trying to retrieve a boat unless the owner gave permission to come back in.

Of course he agreed to bring the men in, and the Coast Guard told him to go back to their hotel and return the next morning. They assured him the boat would wash up on the shore, and they’d find it for him.

Sure enough, Vodicka said, “The next morning they had that boat on our trailer, secure. Of course it was all messed up—it came in upside down, [the waves] broke the console, the motor was smashed. All the expensive tackle, it was gone.”

And that fishing rod and reel that started this whole story? Gone, of course.

“It was a 9-foot spinning rod. I kept it to cast for smaller fish, to be able to cast a long way for what they call mahi mahi now, they’re dolphin. I always had something like that in the boat so I could cast for that, or fish we could use for bait. It would land a pretty big fish, though,” he reminisced.

The one Dudley returned was actually one of the least expensive rods, though it was one of Vodicka’s favorites and most useful.

He guessed that the spinning rod was lighter than the rest of his gear, causing it to be picked up in the trawler’s net. “The others were so big and heavy they probably were buried pretty quickly. This was a lighter thing, it probably got tangled up in something.”

As the afternoon wrapped up at the Cracker Barrel, Vodicka offered to pay for Dudley’s lunch.

“Oh no you’re not,” Dudley replied. “This is a celebration that you’re still alive!”

As for the Fin-Nor reel and the rod, they’re not going to spend any more time on someone’s wall. The reel is being serviced at a repair shop, but Vodicka immediately had the rod reconditioned and used it to go fishing in the Neuse River over Labor Day weekend. “It worked. It worked fine,” he said.

“It’s amazing that after 50 years you get your favorite rod and reel back,” he said.

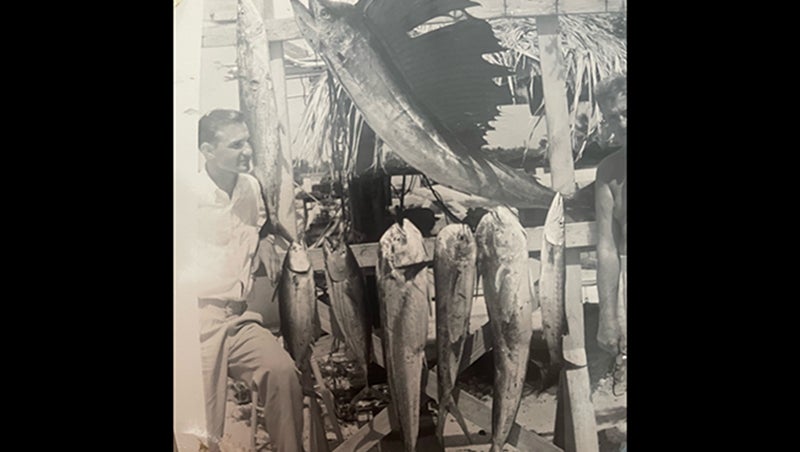

Ralph Vodicka is reunited with his favorite fishing rod and reel after 50 years. Courtesy photo

Editor’s Note: If anyone knows the identity or whereabouts of the little boy in the rescue boat, Mr. Vodicka would like to extend his thanks. Please contact The Coastland Times with any information.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect that the two men met up in Rocky Mount, not High Point as originally reported.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE COASTLAND TIMES TODAY!