The Nature Corner: Critter clues

Published 4:24 pm Wednesday, October 7, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

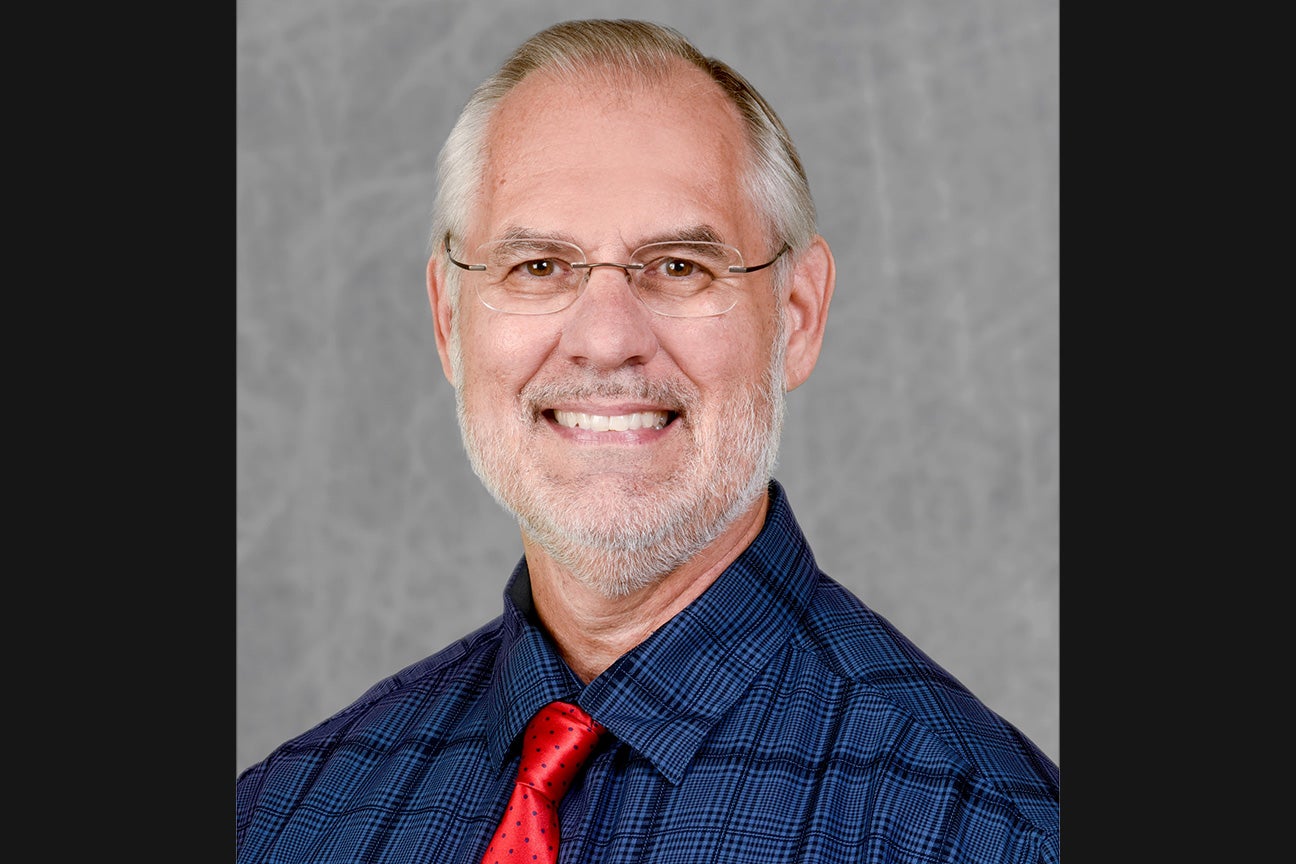

By Ernie Marshall

Years ago, when my son was a mere toddler, my family and I drove the hour and a half from Denton, Texas, the town where I grew up, to Glen Rose to what is now Dinosaur Valley State Park. There is a small museum and a few life-size models of T-Rex and other dinosaurs, but the real attraction was dinosaur tracks in a rock layer along the shores of the Puluxy River, a tributary of the Brazos.

My son toddled off, as he was wont to do, so we went looking and found him sitting in a huge dinosaur track filled with rainwater, big as a washtub. He was splashing in the water and grinning ear to ear. Too bad no one had a camera.

Those dinosaur tracks have born witness to the wanderings of monstrous beasts for over a hundred million years. Most animal tracks are not preserved for the ages in stone, but they nonetheless tell you of an animal on the prowl.

A fun activity with youngsters is to look for animal tracks, best at a park or other such place, and make plaster of Paris casts of what you find. Raccoon and deer tracks are rather common. You need a surface that easily takes footprints, such as a stream bank or dirt road after a rain, and have your supplies with you, plaster, water and something to mix it in. Just pour your wet plaster mixture liberally into the track.

On a warm day, your cast of the track should “set” or be dry enough to remove and take with you on the return leg of your hike.

One of my favorite places to look for animal tracks is the dirt roads in Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. You can often discover black bear, grey fox, bobcat and white-tailed deer tracks. Fresh snow and beach sand are also good sites for animal tracks. (Jockey’s Ridge State Park used to have a workshop in track identification called “Tracks in the Sand.”)

There are many other “critter clues” to be found, signs left by animals, often secretive or nocturnal animals rarely seen. In these difficult days of the corona pandemic, with kids doing school from home and parents and children spending more time in each other’s company, you might want some tips on including a critter clue search in your activities. You can do this as a scavenger/treasure hunt, or as I prefer, just a nature walk exploring for what turns up. Here are some animal signs to look for (besides animal tracks):

- Beaver chews: Signs of beaver such as chewed stumps, have a characteristic look. Beaver typically chew their way around the tree, leaving a pointed stump surrounded by their “chisel like” teeth marks. Beavers are more common than you might suppose. Their populations are generally increasing and they are mostly nocturnal.

- Snake skins: A snake typically sheds its skin at least once a year. It may be hanging in the crotch of a tree, which helped the snake slide out of its old skin. The skin leaves a detailed impression, including skin covering its eyes. And guess what? From the skin you can determine whether the snake is venomous (a cottonmouth, copperhead or rattlesnake) or non-venomous (rat snake, water snake, etc.). The scales on the underside continue as divided past the anal plate with non-venomous snakes; with venomous snakes, they continue as undivided at that point. (Check the internet for a picture to better explain.)

- Cicada skins: Many species of animals periodically shed their skin, but with cicadas it is a bigger deal. An insect’s skin is its skeleton, its exoskeleton, which it wears on the outside rather than inside as we do. You will find cicada skins clinging to trees and such, a perfect replica of the insect, with a slit down its back where it slithered out and went on its way. They are more often heard than seen, making a loud buzzing or droning sound on warm summer days.

- Oakgall: These are a smooth spherical growth (hence sometimes called an “oak apple”) on oak leaves caused by a gall wasp depositing its eggs in a developing leaf bud. Chemicals produced by the hatched larva cause the plant to react by producing the gall, and the larva feeds on the gall until the the adult wasp hatches and flies away. Oh, the shenanigans that go on in nature.

- Sapsucker sapwells: The yellow-bellied sapsucker drills parallel rows of small holes around a tree. The woodpecker does this to get at the sap rather than hidden bugs and grubs. But it is not just for the sap, since the oozing sap attracts insects which the woodpecker returns to feast on. This woodpecker is a winter visitor here because further north, the sap is not flowing until spring. (Most of our woodpecker species are here year-round.)

- Be on the lookout in late spring, around sandy stream banks or on dirt roads for evidence of a raccoon digging up a turtle’s nest of eggs. There will be holes and disturbed soil and empty egg shells (turtle eggs are “leathery,” unlike chicken eggs, and a bit smaller). Pond turtles need to leave the water for dry land to deposit their eggs, or the eggs could “drown.” The raccoon’s sensitive sense of smell can discover where they are buried and find a meal.

Searching for critter clues make you part naturalist and part detective. What happened here and who done it?

Ernie Marshall taught at East Carolina College for thirty-two years and had a home in Hyde County near Swan Quarter. He has done extensive volunteer work at the Mattamuskeet, Pocosin Lakes and Swan Quarter refuges and was chief script writer for wildlife documentaries by STRS Productions on the coastal U.S. National Wildlife Refuges, mostly located on the Outer Banks. Questions or comments? Contact the author at marshalle1922@gmail.com.

FOR MORE COLUMNS AND LETTERS TO THE EDITOR, CHECK OUT OUR OPINION SECTION HERE.