Hearing About 1990 Murder Case: Spencer’s Bid For Trial To Be Pondered

Published 1:05 pm Thursday, April 22, 1993

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

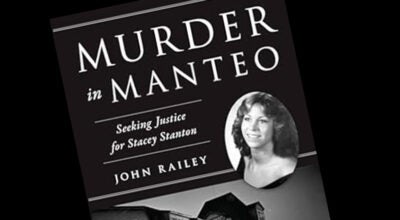

After a day and a half of intense courtroom drama and testimony, Superior Court Judge Gary E. Trawick reserved decision until today (Thursday) on Clifton Eugene Spencer’s motion seeking trial on the state’s charges that he murdered Stacey Stanton.

During the hearing, court-appointed attorney Edgar L. Barnes called hostile, friendly and expert witnesses to testify before Judge Trawick in support of Spencer’s motion for appropriate relief. Defending against the motion was District Attorney H.P. Williams.

Overnight, Judge Trawick must decide if Greensboro attorney RomalIus Murphy provided effective counsel to Spencer, 34, who in 1990 stood accused of first degree murder with death penalty consequences.

In his closing argument, Barnes stated that Murphy was Spencer’s eyes and ears and that Spencer knew what his attorney knew. Barnes contends that Spencer lacked sufficient information to make an intelligent, informed and voluntary decision about the plea he entered into on Jan. 8, 1991.

Barnes attacked on several fronts to present his client’s case. Necessarily, to prove that Murphy did not provide adequate legal representation, Barnes had to attack the sufficiency of evidence which the state brought to bear in the murder of Manteo waitress Stacey Stanton.

Time pays a crucial role in this week’s drama as it did during the investigation and subsequent legal actions.

Stanton’s body was found on the afternoon of Feb. 3, 1990 in her apartment at 506 Ananias Dare Street in Manteo. Manteo’s police chief, at the time Stephen Day, had jurisdiction and he asked Dare County Sheriff’s Department and the State Bureau of Investigation to assist in the investigation.

By the afternoon of Feb. 4, investigators were talking with (Barnes consistently said interrogating) Spencer at the Tyrrell County jail. According to testimony, from Feb. 4 until the morning of Feb. 9, Spencer was without the advice of counsel. During that time, Spencer made several statements and was served with a search warrant for hair cuttings, a blood sample and fingernail clippings. On one occasion he was transported from Tyrrell to Dare County, without court order but with the authorization of then-Tyrrell County Sheriff Roy Brickhouse. At this time, Spencer was being held on outstanding drug charges in New Jersey.

On the morning of Feb. 9 and again on Feb. 23 and Feb. 28, Spencer was interviewed by investigators, but on these occasions Columbia attorney Charles Ogletree was present.

On March 12, Spencer, now in New Jersey, was served with a warrant. Spencer fought extradition, but lost and was returned to Dare County on June 1.

Without preamble, Edgar Barnes called as the first witness, attorney Romallus Murphy. Murphy said he was retained, by whom he could not specifically remember, in early June to represent Spencer. He notified the district attorney of his representation and on June 19 filed a request for appointed co-counsel and on June 21 filed a request for discovery.

According to testimony, from the end of June until Jan. 7, Murphy filed no motions in court. On Jan. 7, he filed various, and standard, pre-trial motions for capital cases.

The district attorney’s office responded to the discovery request, which basically says “show us what you have against us,” on Nov. 28, 1990.

Murphy said “delay is an advantage” and affirmed that black/white relations was an issue in the case. According to Murphy, time would help diffuse tensions surrounding the case of a black man accused of killing a white woman.

Murphy’s co-counsel, David M. Dansby Jr., a Greensboro attorney who shares offices with Murphy, stated that “speed is not important”

One week following the delivery of the discovery materials on Dec. 7, 1990, district attorney H.P. Williams wrote Murphy offering a plea arrangement.

On Jan. 8, 1991, Spencer stood in open court and accepted that plea of “no contest” to second degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison by now retired Judge Herbert Small.

Overnight, Judge Trawick will review the exhibits, the discovery material, copies of case law submitted by district attorney Williams, a brief turned in by Barnes and his own courtroom notes, and the judge will sort out these contentions:

– Under the standards set down by the American Bar Association and those that are normally practiced in Dare County, did attorney Murphy pursue the defense of his client in such a manner as to offer Spencer the information and advice needed to make an informed decision?

– What weight should be assigned to Spencer’s unrecorded and unsigned statements? On the witness stand, Spencer said Murphy only gave him the statements from the discovery materials and told him “there was no way I could win this case.”

– If Murphy had filed a motion to suppress all or part of those statements, which he did not, is the state’s case strong enough to prevail? Murphy averred that on January 8, he came to a motion and scheduling hearing rather than a plea session and that he would have analyzed those statements in time for trial and filed appropriate motions.

– Barnes contends that without independent investigation, such as interviewing witnesses and talking with investigation officers, the strength of the state’s case could not be assessed and therefore Spencer could not be properly informed or advised about any plea arrangement. Two attorneys affirmed that some investigation was called for before advising about a plea.

Motions for appropriate relief seeking new trials based on attorney actions are routinely filed and just as routinely dismissed. The Spencer case is unusual in that the motion has made it to the hearing stage and that it is based on a conviction without trial.

Beginning on Tuesday morning, Barnes called 16 witnesses to the stand in the civil courtroom of Dare County District Court.

In addition to attorneys Murphy and Dansby, Barnes questioned members of the investigating team special agents for the State Bureau of Investigation Dennis G. Honneycut and Kent Inscoe and Lt. Col. T. Jasper Williams with the Dare County Sheriff’s office. Inscoe said, under cross-examination by Williams, that at every step in the questioning process, Spencer had been advised of his fifth amendment rights to have an attorney present.

But Spencer’s sister Karen followed and stopped H.P. Williams’ acerbic questioning cold. Karen Spencer had testified that her brother said he was not read his rights. But, Williams said that in fact she had just learned that was not true from Inscoe’s testimony. Ms. Spencer said, “I can’t say that I have. ”

Spencer’s initial attorney, Charles Ogletree, was called to the stand as was Tyrrell sheriff Ray Brickhouse and former Manteo chief Stephen Day.

Two of Spencer’s collaborative witnesses were called: Wayne Morris, who lives in Greenwood Acres Trailer Park, said Spencer walked to his trailer around 4:30 a.m. on Feb. 3 (night of the crime) and went to sleep. Dale Burrus, a friend, said he picked up Spencer in front of the Pizza Hut on the morning after the crime and took Spencer back to Columbia.

Following these two witnesses, Barnes called family members including Walter Spencer, a first cousin twice removed, Spencer’s father Harry and his mother, Emma Jean.

Following Spencer’s testimony, Barnes’ case presentation concluded with testimony by Dare County attorney Mark Spence, who had been asked by Barnes to review the existing court file. Spence, in addition to reviewing discovery material, talked with Spencer, Williams, Murphy and Barnes.

In a pre-hearing motion, Judge Trawick quashed a subpoena issued to reporter Jon Glass, but admitted into evidence an article written by Glass and published in “The Virginian Pilot” after Spencer’s no contest plea was entered.

To see the scans of the archived newspaper page where this article appeared, click here.

READ MORE ARTICLES RELATED TO THE STANTON CASE HERE.